Part 3: Case-Studies

Both domestic and international travels have been heavily limited in the fight to limit the spreading of COVID-19 and breaking the curve. Many countries and their population managed this in the first wave quite well, thanks to their strong economy and wealth. Others, as many as 100 countries and especially their poverty stricken population are struggling, forced into compromises. This series of publications seeks to spark further thoughts into a responsible international travel scheme during this and future pandemics. Part 1 covered the general assumptions and boundaries, reflections on risk management and commercial impacts. Part 2 studied tools and processes that might lead the way to an open new normal. Part 3 expands on some select case-studies currently deployed and discusses some up- and downsides. Part 4 elaborates on the travel industry in change. Part 5 sheds some light on various solution components and how they fall in place.

By Stephan D. Hofstetter, Managing Partner SECOIA Executive Consultants Ltd

In part 2 of this series we reviewed the various data that could be used for risk assessment and how this data could be generated and processed. In this third part we will take a practical approach and look at some specific national implementations. What is being done and what are the lessons to be learned, from the positive and from the weaknesses.

In preparation for this short essay, we have examined about 100 countries for their current implementation with regard to travellers wishing to immigrate to their territory. Where differences exist, we take into account foreigners and nationals as well as leisure and business travellers. It is expected that the data will be very volatile and changes may occur at any time. Therefore, it should not be assumed that the data represent a legal basis for personal travel arrangements or other intentions. It should only be used as a source of inspiration and in the interest of this discussion. We will discuss three basic scenarios: The restrictive suspension or severely restricted freedom to travel, the liberal freedom to travel within so called "travel bubbles" and the managed screening programmes before boarding. The focus will be on the latter.

Restricted or no travel (Lock-down)

The list of countries with absolute travel bans for foreigners is long and ranges from Japan to most African countries. More often, countries have closed their borders to certain countries with poor pandemic indicators or established a small exception window for entry, supplemented by 14-day quarantines. These windows may be available due to family obligations, for example.

Travel within bubbles

Travel bubbles, also known as travel corridors and corona corridors, are essentially an exclusive partnership between neighbouring or nearby countries that have had considerable success in containing and combating the COVID-19 pandemic within their respective borders. These countries then restore the links between them by opening the borders and allowing people to move freely within the zone without having to undergo quarantine upon arrival.

The spread of the concept was promoted by the three Baltic States, namely Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, when they established a trilateral partnership which allowed citizens of these countries to enter the territories of the Member States. This free passage was eventually to be called the 'travel bubble'.

There are several travel bubbles in Europe. Two examples are the travel bubbles between Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Liechtenstein and neighbouring eastern European countries. A second bubble exists between the two Scandinavian countries Denmark and Norway. Sweden was excluded because of the still very negative development of its COVID case numbers.

In the Asia-Pacific region there are many bubbles that already exist or are developing. Intensive talks are currently taking place between Australia and New Zealand on the creation of a Trans-Tasman travel bubble. There is still a way to create it, as the state of response to the local impact of the pandemic is at very different levels. Another example is between China and South Korea, which have implemented a corona bridge since May 2020. This bubble connects only selected cities, including the economic centres of Seoul and Shanghai. It could be extended to the special administrative zones of Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau.

Intensive talks are taking place on the American continent. Colombia is seeking agreements with its neighbours. However, the freedom of travel between the USA and Canada has experienced some restrictions that only allow authorized persons to travel.

No travel bubble arrangements have been made in Africa.

Setting up safe travel corridors are a welcome manner to facilitate commerce and freedom to travel. However, they are complex to be managed by the various stakeholders including the airline operators. They are subject to rapid changes as the case-numbers develop. And they are not suitable to contain the pandemic.

Screening prior to boarding

This solution concept is based on the Passenger Location Form (PLF), the Health Declaration Form (HDF) and the Advanced Passenger Information (API) concept, which aims at a prepared risk assessment before the passenger arrives at the border.

The overview below provides a snapshot of implementations in selected countries around the world. The quality and methodology of implementation varies widely. Some forms function essentially like paper forms, with little plausibility checking and interaction. Others have a higher level of user guidance and support for passengers. All in all, most implementations miss to capture the information for a meaningful, automated processing and cross-checking of the submitted data. The authorities could argue that the passenger confirms that the data has been filled in correctly and is legally bound by the answers. However, the idea of pre-processing the data in advance, which prevents people from travelling at all or ground staff being ready for immediate health and hygiene measures, cannot be adequately achieved.

Download document here. Use with reference to authors.

Looking into some specific country-implementations

Greece: Passengers from 14 non-EU countries are subject to this procedure and must visit a website at any time before their journey, but at least 2 days before. The issues raised are very similar to the forms distributed in the aircraft for arrival. Greece has chosen not to ask actual health questions and focuses on where a person was before travelling (countries visited) and where they could be contacted during their stay in Greece. Upon completion, the passenger will receive a document with a QR code, which can be downloaded directly from the website and will be sent by e-mail a few days before the trip. This document contains a QR code and some basic identification information. On arrival at the health authorities at the border, this QR code is scanned and further steps are taken based on the prepared risk assessment. Dimitris Paraskevis, associate professor of epidemiology at the National and Capodistrian University of Athens and member of the expert committee dealing with the pandemic, says that “the particular algorithm will be able to detect the majority of imported cases.”. During the preparations for this article an update was made: As of Wednesday, July 15, 2020, all travellers entering Greece via the Promachonas border station for non-essential reasons will be required to present a negative molecular test result (PCR) for COVID-19 upon arrival, which was performed up to 72 hours before entering Greece. Travellers should be tested in the laboratory with RT-PCR of oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal swabs.

Jamaica: Passengers must complete an online PLF-Form. On the website, the Jamaican authorities present a remarkably transparent and well presented procedure so that visitors can understand the specific procedures applicable to their trip. The registration process begins with a challenge-response process to the presented email, ensuring that the authorities have a reliable way to reach the traveller. Further data collection is more standardised, with a specific mix of risk exposure questions. Uniquely the profession of the traveller is inquired, based on a fixed set of options. We assume there are risk profiles attributed to the professions. Another point that differs from other implementations is that in most cases, travellers are required to download the governmental tracking app, including GPS tracking. To limit the risk of leaving such a device in the hotel, an audio-visual recording is required for registration. Occasionally, the user will be prompted to provide additional audio/visual evidence that the device is being carried.

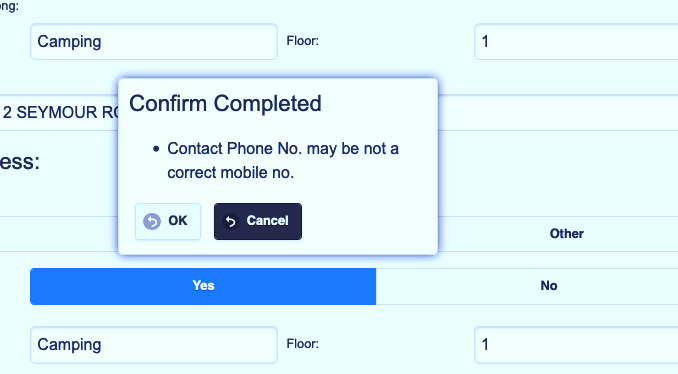

Hong Kong: For travellers to the Hong Kong SAR, there is an online Health Declaration Form that must be completed maximum three days before travel. It is valid for air, land and sea transportation. Only a very basic validation of contact details is carried out. However, this is the only reviewed implementation that has a plausibility check on the phone number. The implementation for the local contact details, especially for hotel guests, helps to avoid mistakes. The survey on risk exposure is not very detailed. Based on the profiling, the authorities distribute tracking devices that have to be carried at all times.

Spain: We will not discuss the process implemented in Spain into detail and point out to a noteworthy aspect. From the samples listed here, Spain is the only implementation issuing an actual discouraging of travel based on the immediate assessment of the answers. "HEALTH RECOMMENDATION: Based on your responses, it would be advisable not to travel to Spain. If you do so, it will be your responsibility, and you must adopt all the sanitary measures indicated by the health personnel at the airport, in addition to committing to everything indicated in the signature of this form."

These implementations have the advantage that they can be implemented quickly. However, the actual value is not clear due to the intransparent algorithms. They also lack the actual validation of the data: No validation of contact data (challenge-response from email / phone), to link to API data (i.e. non-existing flights, wrong dates and ports of entry could be entered), deadlines for providing the information were sometimes not enforced, and the health screening questions might serve liability requirements, but not actual management of the pandemics. With learnings being taken seriously and evidence from science filling in, this path is very promising.

Assessment of pre-boarding screening

The biggest weaknesses of the current implementations of the pre-boarding screenings are:

The initiatives are not harmonized, lacking guidance and common policy rules. The international organizations such as CAPSCA, ICAO or IATA are yet to provide guidance on best practice. This causes insecurities for passengers, opens loopholes and slows down progress on a global scale

The captured data is not standardized and not validated, making it difficult or even not practical to actually run machine-based assessment for an actual pre-travel screening. Making use of entry validations via predefined pull-downs, focussed on the actual intention of assessment is to be considered. Failing to do so will be perceived by passengers as an administrative hassle.

Digital contact data is mostly unvalidated, although it would be a simple step to be improved: Challenge-response eMails as implemented by Jamaica or SMS-Validation of mobile phone numbers are standard services. In the same run, a blocking of one-time eMail providers would further enhance the certainty of being able to contact the passenger in case of need.

Being able to make use of existing risk assessment procedures would be of great value, preventing isolated patchworking. Many countries have existing API/PNR-review mechanisms, allowing sometimes even recent travel pattern validation. In order to make this work, there is a need of acquiring the according keys: Passport Number is one of them, linking the application to a travel document. The other would be the request of booking reference, allowing to populate or validate Flight information, place of embarking, place of arrival, time, and perhaps even hinting on the days of remaining in the country.

The questions related to the COVID-risk exposure are in many cases very generic, and appear rather random. While most of the above referenced countries do ask about individual symptoms, they often lack to grab all of the currently known major indicators, such as loss of taste. Also, they might ask about having tested COVID-19 in the past. However, in one case there is no question about it being positive or negative (Jamaica). Others only ask if the test was positive anytime in the past. This practice could mean, the person is still infectuous, or he might have overcome the disease and might have an unverified immunity. An evidence-based evaluation of these generic questions remains unclear.

Knowledge of best practice is still limited. However, the various schemes provide an invaluable source of inspiration for assessing more effective ways to facilitate responsible international travel. Many measures appear to have been implemented in a short time and with few resources. Some could serve as a fig leaf rather than an actual management tool. Finally, some of the implementations, such as in Jamaica, are groundbreaking in terms of what could be done, although it would not be possible for several countries for data protection reasons. The next article will deal with the take-aways of the status quo.

Please do not hesitate to comment in a constructive and solution-oriented manner. We look forward to further developing the approach together with the professional community.

About SECOIA Executive Consultants Ltd

We are a network of experienced professionals working in the public sector and specialized industry. Our mission is to consult the involved parties and join needs and solutions as match makers. We oversee the identification of requirements, development, evaluation, search and implementation.

Comments